Similar to years prior, I was delighted to be asked to speak at the 2025 CarMax DevOps Days Internal Developer Conference. I didn’t have to cast about for a topic very long; the rash of cost optimization and benefit rationalization conversations happening across industries have platform owners on their heels. So I decided we needed to talk about it.

Some of the slides had auto-looping GIFs in the background. However, in creating the web version, I dropped the animation; the transitions still made sense without them. The slides and speaking script are below - enjoy!

In today’s climate, every software investment is under scrutiny, and Internal Developer Platforms (or IDPs) that can’t demonstrate short-term value are on the chopping block. Yet many IDPs built in the last decade are now invisible; assumed rather than celebrated. This talk offers a survival guide: why invisibility is dangerous, how macroeconomic pressures magnify the risk, and some practical steps to avoid the worst of the downsides.

As was mentioned, my name is Matthew, and I’ve worn many hats over the years. I’ve been a software developer, an architect, product manager, writer, speaker, conference organizer, entrepreneur, and more.

I’ve reached the point where I’ve decided if I’m going to wear a label, it might as well be one that I’ve made up. For now, I refer to myself as a software change anthropologist.

I coach enterprises on software platform, governance, and change initiatives. Often that means bridging the canyon between technology ambition and actual business value.

I’ve had the pleasure of speaking at DevOps days multiple times in the past on topics as varied as soft skills and AI. Some of those previous presentations include:

- 2024 – Surviving the Turbo Encabulator

- 2023 – Separating AI Fact from Fiction

- 2022 – Seven Skills to Change Complex Systems

- 2021 – We Made an API Description, Now What?

But during my work with enterprises, I’ve seen a disturbing trend that became the basis for this talk. Today I want to talk about the imminent peril many internal developer platforms find themselves in.

First, I’ll illustrate the challenge many of us face, a paradox in platform engineering: the better our platforms work, the less visible they become. I’ll explain why that’s dangerous, and I’ll highlight three patterns associated with invisibility:

- reactive investment cycles

- the loss of champions

- finance’s tendency to classify platforms as overhead

Then I’ll share a case study from my own experience that illustrates how even state-of-the-art platforms can drift into neglect if they’re not actively supported.

Finally, I’ll present three solutions I’ve found to be effective; strategies you can take back to your organization to help keep your platform relevant, funded, and visible.

My goal is that you leave here not just with a new insight or two, but with practical approaches you can apply to ensure your internal developer platforms remain recognized as essential to your company’s success and don’t become invisible plumbing.

Even if you don’t interact with an Internal Developer Platform (or IDP) daily as part of your job, I guarantee you there are others in your org that do. These critical pieces of software might be an API developer portal, cloud offerings like AWS Proton, Azure Developer Hub, or Google Cloud deploy, or even internal CMSs for knowledge management.

This software infrastructure has become big business, with some of the biggest software names offering managed solutions. But it wasn’t always this way.

The push for automating common tasks and providing shared infrastructure is a relatively new phenomenon.

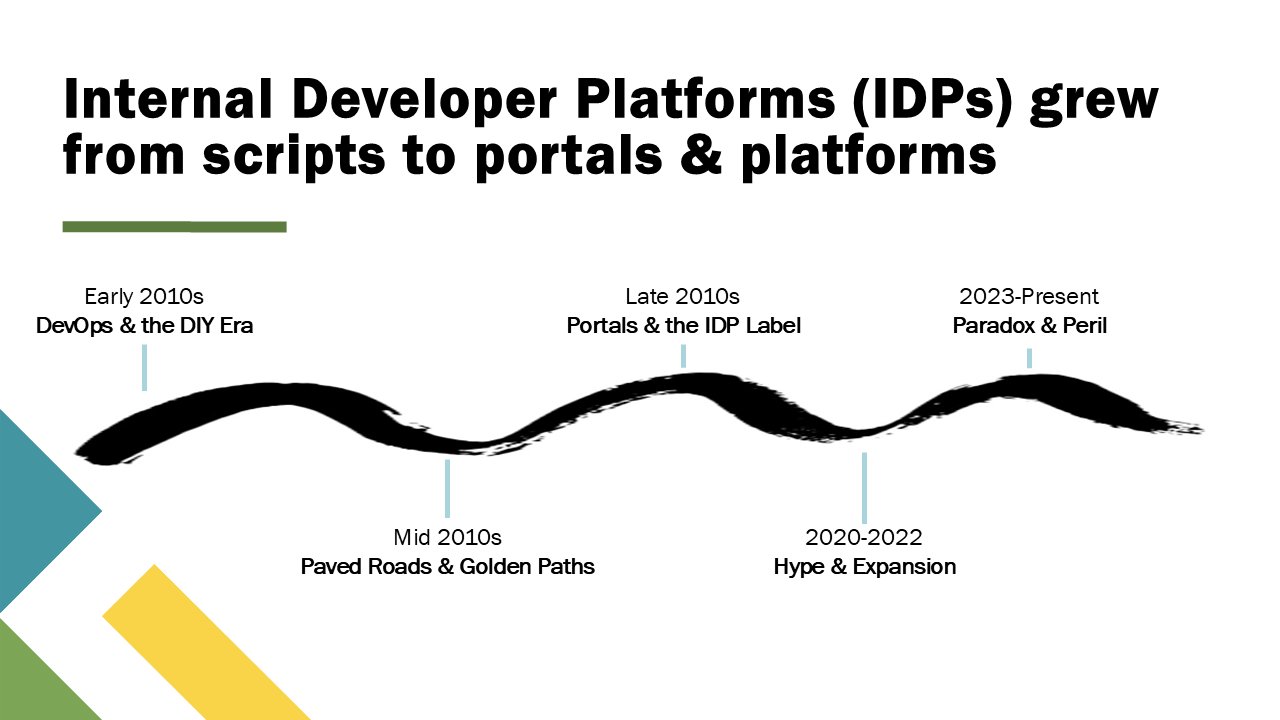

A Brief History of Internal Developer Platforms (IDPs)

Early 2010s: DevOps and the DIY Era

- The term “DevOps” was coined in 2009 and spread rapidly. Teams began stitching together their own toolchains for CI/CD, infrastructure automation, and monitoring.

- Hallmarks of these tentative first steps were often ad hoc scripts, Jenkins jobs, and wiki pages that worked locally but didn’t scale.

- The first “platform teams” emerged to provide reusable pipelines and guardrails.

Mid-2010s: Paved Roads and Golden Paths

- Large tech firms (Netflix, Spotify, Google) started publishing about “paved roads” or “golden paths” — curated ways to build and deploy software safely.

- These weren’t yet packaged as platforms, but the concept of self-service developer experience took shape: one place to go to create a service, get a pipeline, and deploy.

Late 2010s: Portals and the IDP Label

- Tools like Backstage (from Spotify, 2019) and open-source frameworks gave a name and face to these efforts.

- Analyst firms (Gartner, Forrester) began writing about IDPs, as a category, something distinct from raw Kubernetes, CI/CD, or cloud infrastructure.

- The framing shifted: IDPs weren’t just tech; they were products offered internally, with dedicated development teams, roadmaps, docs, and support.

2020–2022: Hype and Expansion

- CNCF talks, venture-backed startups, and blog posts proliferated. IDPs became “so hot right now.”

- The promise: accelerate developer productivity, enforce standards, reduce cognitive load.

- Many organizations launched portal initiatives to catch the wave, often anchored on Kubernetes and API governance considering companies discovering they were now liable for an explosion of microservices without a means of managing them responsibly.

2023–Present: Paradox and Peril

Today, unprecedented system shocks and geo-political instability are redefining company IT spending. Today’s challenge isn’t proving that IDPs work but proving that they matter: making their invisible value visible to finance and leadership.

In other words: IDPs grew from scripts to portals to platforms. By 2026, Gartner predicts that 80% of organizations will have platform engineering programs – but the firm also reported that platform engineering has fallen from its height of hype into the “trough of disillusionment”.

They solved real pain, got hyped, and now face the paradox of success: invisibility.

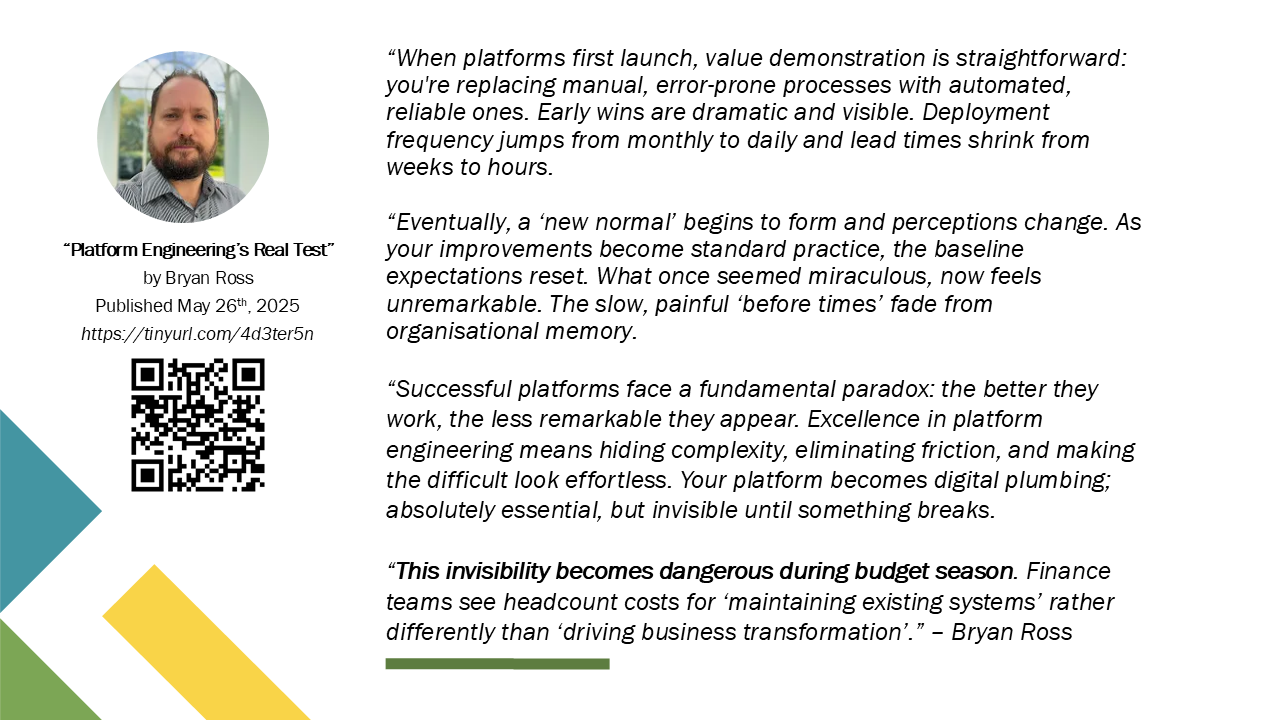

I could attempt to paint a picture of what I see happening across the industry right now, but recently I came across a post by GitLab’s Field CTO, Bryan Ross. It so beautifully captures this unique moment, defining this moment’s paradox, that it is worth spending a few moments on it.

No one’s saying, ‘don’t transform’ or ‘internal developer platforms are bad’. What has changed is that everyone’s doing spreadsheet math now.

Why is that?

It used to be that internal platforms were safe from scrutiny. However, times have changed, and – trust me – your organization’s finance and accounting departments have been put through a wringer to identify where the money is going.

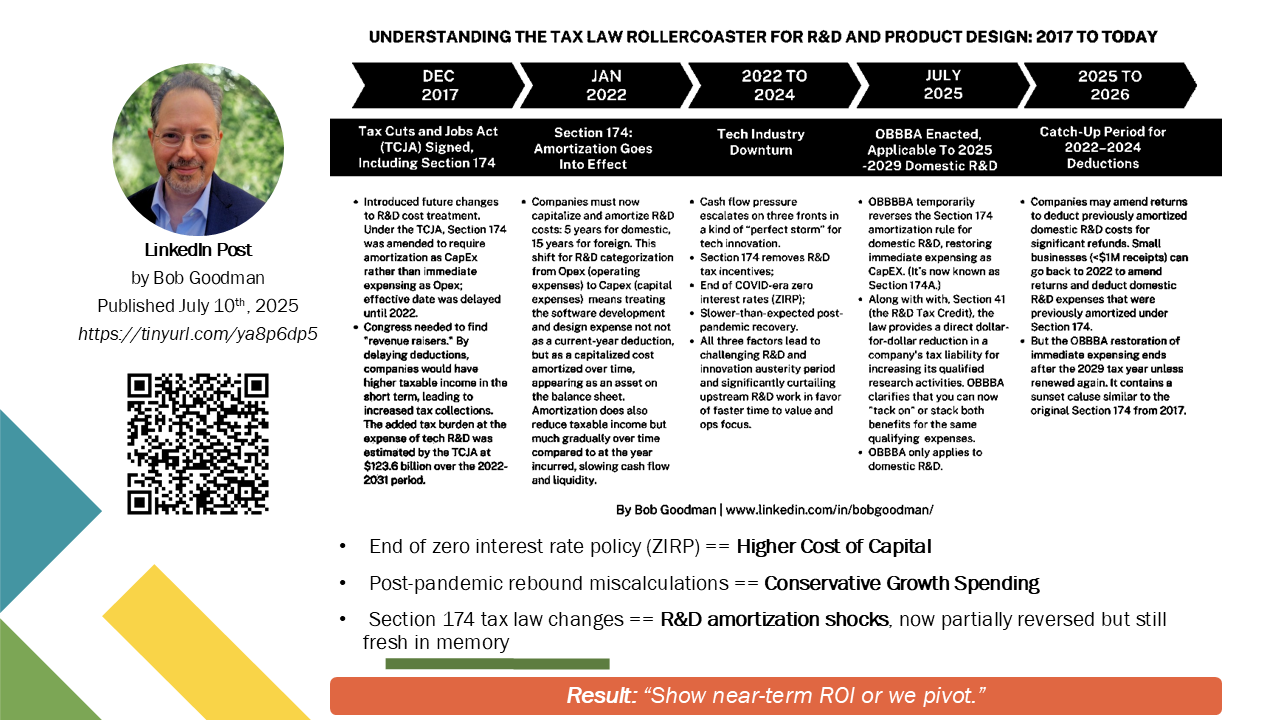

Bob Goodman, a strategy executive, has an excellent summary of how turbulent a normally stable area has been. I’ll leave reading the detailed breakdown as an exercise for the reader. But, broadly, the unexpected shifting of tectonic financial plates can be group in three big, massive moves:

- End of zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) == Higher Cost of Capital == less “free” money available for infrastructure build outs

- Post-pandemic rebound miscalculations == Conservative Growth Spending == the “coiled spring” of consumer demand that was assumed to be building during the pandemic never “sprung”, resulting in lowered revenue realities

- Section 174 tax law changes == R&D amortization shocks, now partially reversed but still fresh in memory == platforms which may have been amortized over years (and thus reducing expense on any single year) now were expensed all at once, again reducing perceived revenue.

The end result is leadership demanding near-term ROI or threatening they will pivot – even for platforms that were once pitched as long-term bets. CIOs can’t afford another modernization failure.

Why is this happening? The answer is money.

The answer is always money.

We’ve talked about why this is happening, but how does this happen? How can an internal developer platform be released with such fanfare and high hopes only to be on such shaky ground a few years later?

The first reason why platforms get into this situation is because of how they’re funded after launch.

Think of your home gutters. On sunny days, you never think about them. Even when they are working as intended, you don’t sing their praises or give them even an ounce of attention. It is only when there is a problem, when they clog and overflow in a sudden downpour, they become an urgent pain to deal with.

Internal platforms work the same way. Their success makes them invisible, which means funding often follows a reactive, ‘as-needed’ model. The danger is that by only investing when something breaks, you let small issues accumulate into big, costly crises.

Invisible systems drift into a break/fix funding model.

Platforms, like gutters, need regular, proactive care to ensure they can continue to perform when stressed. Otherwise, the foundations you rely on every day become fragile, and you pay more later for problems that could have been avoided.

The second reason why internal developer platforms are threatened is that many of their original advocates are no longer there. And without them, the organizational memory of what problem the platform solved has faded.

Champions are the people who remind leadership of the platform’s value, fight for budgets, and keep the story alive.

The problem is, those people often move on. And within most companies, platform work doesn’t carry the same prestige as building customer-facing features or new innovations. Ambitious people want visibility, advancement, and resources, so they leave the platform team for shinier opportunities. Without champions, platforms are quickly forgotten, and their reputation erodes into ‘that thing in maintenance mode’.

And if a platform is seen as now being composed of ‘B’ players, that can pose a challenge during budgeting time, as well.

The third reason why this happens is that finance frames platforms as business as usual (or BAU) overhead, not innovation.

Even if, as a platform owner, you’re able to secure ongoing headcount, finance often doesn’t view that work as transformational or an investment in growth. Instead, they categorize it as overhead. That’s bad for two major reasons:

- It undervalues crucial ongoing work that will enable the next big thing to happen

- Makes any platform an easy target during cuts (“let’s redistribute headcount to growth initiatives”)

Transformation is exciting; maintenance is not. Innovation is allowed to incubate. Operations are ruthlessly optimized as if it were a mature implementation.

Platforms are like mowing the lawn: you’re never truly done. If you stop, things overgrow, break down, and cost more to repair later. But regular lawn care can get overlooked by one-off, new, shiny objects.

I know these forces exist because I’ve personally seen them play out. A few jobs ago, I had the pleasure of contributing to a fantastic, homegrown API developer exchange. When we launched it in 2015, it was genuinely state-of-the-art. Developers could submit an OpenAPI description, and have it go through an editorial workflow for design review. Once approved, the API description would be automatically published to our internal portal, initiating the corresponding environmental setup. There was nothing else like it in the industry. In fact, there was a moment when we even considered open-sourcing it, and this was several years before Spotify released Backstage. That’s how ahead of the curve we were when it came to a structured, platform approach to our API program.

But platforms don’t stay cutting edge on their own. We soon had challenges. While we had launched with OpenAPI 2.0 (or Swagger) support, adding OpenAPI 3.0 lagged behind other priorities. While vendors raced ahead, our platform stayed stuck. Meanwhile, new needs emerged - data, compliance, other protocols - but investment in the platform remained limited. Without champions, without funding framed as innovation, our home-grown tool became more of a burden than an enabler. Eventually, it was eclipsed by other tools. What started as a crown jewel ended up as an Achilles’ heel.

And this isn’t just my story. It’s the same pattern I’ve seen over and over again: an internally built tool feels special at the start. It demonstrates brilliance. But without continuous investment, without telling the story of why it matters, it falls behind. And when new hires look at it, they wonder why we didn’t just use an off-the-shelf solution in the first place. By the time leadership makes the switch, you’ve already paid the cost twice - first in building, then in abandoning it.

This is exactly why invisible platforms are so dangerous. Left unattended, they rot quietly until failure or replacement forces a reckoning. And by then, the costs are far greater than steady, proactive investment would have been.

This can feel unfair. We may want to lash out at the systems as being unfair or unjust.

However, there are far more productive ways of going about ensuring platforms remain relevant within your organizations. These recommendations aren’t just based on theoretical, but lots and lots of reflection on just what exactly I could have done better as a platform steward.

Building the platform isn’t enough. You also need to tell the story of what it does. Left alone, people forget how bad things were before. They reset their expectations and stop noticing your impact. Narrative work means showing the before-and-after, in terms business leaders care about. If you don’t make the value visible, it may as well not exist.

When I pushed for OpenAPI 3.0 support, my message was all about technical currency: “This is the newest version, and we must remain current.” That might have resonated with engineers, but it didn’t land with business leaders. To them, the story sounded like unnecessary tinkering. If I had framed the narrative differently - for example, how supporting OpenAPI 3.0 would unlock faster partner onboarding, reduce manual review cycles, and align us with external vendors - the value would have been clearer. Without that story, my ask felt abstract, and the investment didn’t follow.

Every platform produces numbers. But most don’t matter to the people holding the budget. Counting services onboarded or uptime doesn’t tell finance or executives why the platform is valuable. The right metrics connect directly to business impact: time saved, cost avoided, risk reduced. And they should be trended over time to show progress, not just raw figures. Metrics are the evidence for your narrative.”

When making the case for OpenAPI 3.0, I had no metrics that mattered outside the platform team. I could point to “number of services asking for OpenAPI 3.0” or “percentage of APIs wanting to use new features,” but those were outputs, not outcomes. What I couldn’t show was how our platform’s limitation translated into developer time lost, longer onboarding for consuming teams, or how being perceived as “outdated” was eroding trust. Without metrics that tied directly to business impact, my case felt like a trivial detail instead of a productivity bottleneck or risk reduction opportunity.

If the platform doesn’t help the right people achieve their goals, it will get bounced around like a hot potato. Tech leads, finance, product, executives all need to see the platform as advancing their own priorities. Stakeholder mapping means aligning your story and metrics to each audience. When they can point to the platform as the reason they succeeded, that’s when funding and support are sustained.

The failure to get OpenAPI 3.0 prioritized was also my failure to properly understand what my executive stakeholders needed to hear. Tech leads cared about compatibility and reuse, but product management only saw another competing priority. Leads didn’t see how this helped deliver features faster, and executives weren’t convinced it tied to strategic goals.

To each of them, doing the work to add 3.0 support looked like a platform tax, not a platform win. Had I mapped the upgrade to each stakeholder’s priorities - reduced integration risk for product, clearer compliance guarantees for executives, lower support costs for finance - I might have built the coalition needed to secure investment.

When it comes to owning a platform, it can sometimes seem like the train has already left the station. Like the best we can do is hang on for dear life before it inevitably runs off the rails.

However, as I’ve hopefully shown, by being more mindful in how we talk about internal developer platforms, we can change the story.

If you remember anything from this presentation, let it be these three points.

- Tell the story: don’t let the problem your platform solved value fade into the past.

- Show the right metrics: connect your work to outcomes that matter. Vanity metrics may be easy to gather, but they mean nothing to others.

- And understand what your leaders need to win: ensure every stakeholder can point to the platform as a reason for their success. That’s how platforms stay visible, funded, and trusted.

Last year, in my DevOpsDays talk, I talked about the dangers of hyperbole. In Surviving the Turbo Encabulator, I laid out a framework for evaluating the outlandish claims that swirl around our industry (Crypto! The Metaverse! AI!). These claims are the bold promises that, if left unchecked, steer teams into wasted effort and false confidence. The message last year was that exaggerated visibility – the hype - is dangerous to your long term, professional success.

This year, I’ve tried to show the opposite extreme: invisibility. These are the platforms that work so well they fade from memory, becoming plumbing in the walls or gutters on the roof. When that happens, the story disappears, the champions drift away, and finance sees only overhead. Invisibility doesn’t provoke bold, bad bets like hype. Instead, it invites neglect. And neglect is just as perilous, because if no one sees the value you’re providing, it might as well not exist.

So on one end of the spectrum, we have hype: noisy, over-promised technologies that overinflate their importance. On the other end, we have invisibility: quiet, underappreciated systems that erode because they aren’t connected to narrative, metrics, or stakeholder wins. Both extremes are perilous in different ways. The real work, our work as people who care about what we do and want to be better, is to steer a middle path. To build platforms with substance, but also to tell the story. To keep them relevant, visible, and sustainable without falling into either exaggeration or a memory hole.

That’s the challenge I want to leave you with: how do you make your platforms visible enough to be valued, but grounded enough to be trusted?

Thank you so much.

Like my other presentations, I will have the extended script and slides posted to my personal website, matthewreinbold.com.

In addition to that site, you can also find my writing at my email newsletter, Net API Notes. Finally, if you’re on the Fediverse – like on the Mastodon platform – and would like to continue this conversation, you can find me at opinuendo.com/@matthew; I’d love to hear from you directly.

Again, thank you for this opportunity and your attention.