It is an honor to be asked back to speak at DevOps Days. Two years ago, I covered seven soft skills for making software change happen. Last year, during the heights of generative AI hype, I did a deep dive showing practical ways generative AI could assist API development. This year, maybe more than any previous year, I have to wade through propaganda, misinformation, and outright lies - and I’m not talking about the election!

Perhaps more than any other industry, software is drowning in bold claims, wild speculation, and outright exaggeration. These muddied messages about what is and is not effective impact our ability to do our best work.

When I say claim, I refer to a statement or assertion that promises specific benefits, capabilities, or outcomes. These claims are typically used to generate excitement, attract investment, or even sow confusion. They range from a modest list of apparent facts to grandiose statements about revolutionary change.

In this presentation, I’ll:

- Introduce you to the claims made by the Turbo Encabulator

- Explain why this 80-year-old engineering in-joke is more relevant to our age than ever before

- Use examples from it and other sources to illustrate the techniques and outline how we might better evaluate the claims that come our way

To understand the Turbo Encabulator relevance to our work today, we first need a bit of history.

In 1944, a British engineering grad student named John Hellins Quick wrote an article for the Institute of Electrical Engineers, Students Quarterly Journal. His studies inspired the satirical description of a revolutionary technology comprised of long strings of meaningless jargon. It went something like this:

“The original machine had a base-plate of prefabulated aluminite, surmounted by a malleable logarithmic casing in such a way that the two main spurving bearings were in a direct line with the pentametric fan. The latter consisted simply of six hydrocoptic marzlevanes, so fitted to the ambifacient lunar waneshaft that side fumbling was effectively prevented. The main winding was of the normal lotus-o-delta type placed in panendermic semi-bovoid slots in the stator, every seventh conductor being connected by a non-reversible tremie pipe to the differential girdlespring on the “up” end of the grammeters-“ — John Hellins Quick, 2nd paragraph of “The turbo-encabulator in industry”, Students’ Quarterly Journal, Vol. 15, Iss. 58, p. 22 (December 1944)

It went on like this for several additional paragraphs.

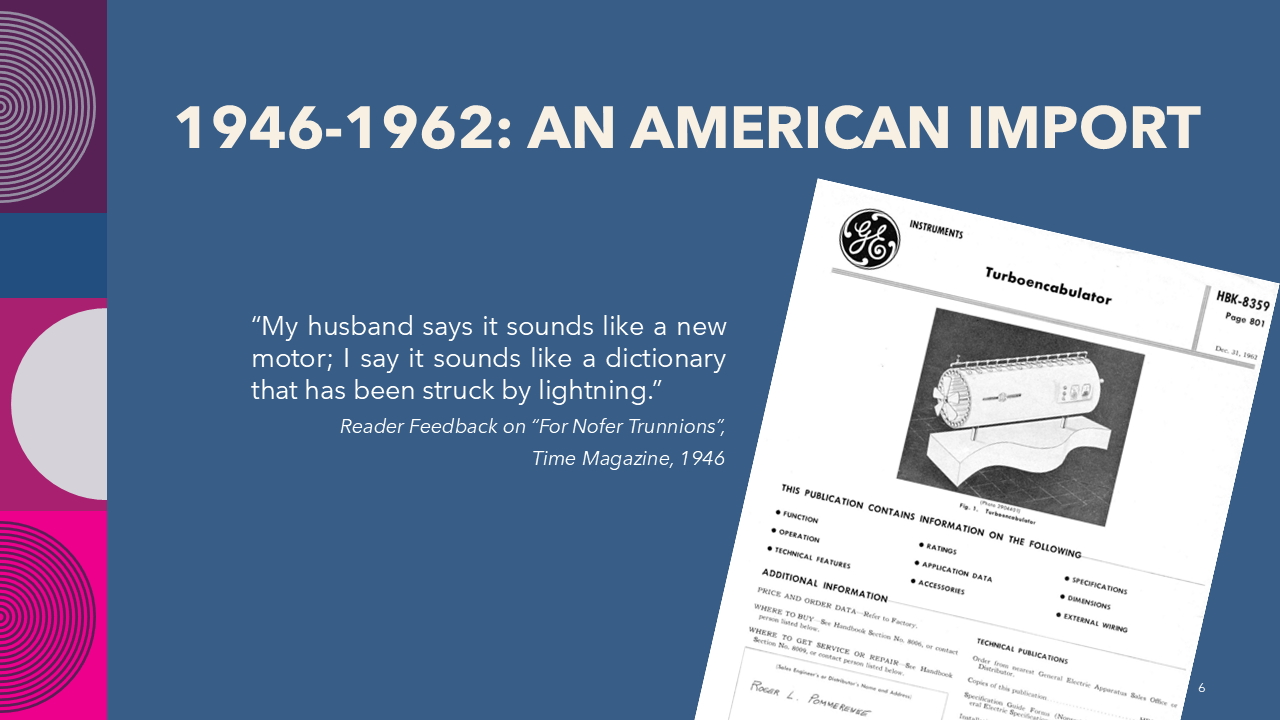

World War II brought rapid advancements in electronics, computing, and telecommunications. Post-war Great Britain was not the only country transformed (and, ultimately, having to adapt) to increase technology sophistication. In the United States, industries were just as impacted. And, like Great Britain, those in the United States challenged to comprehend technobabble and jargon found the Turbo Encabulator just as funny. Or at least some did.

In May of 1946, Time magazine published excerpts from the article under the title, “For Nofer Trunnions”. Reader feedback was mixed. One letter said, “My husband says it sounds like a new motor; I say it sounds like a dictionary that has been struck by lightning.”

In 1962, General Electric even published a data specification sheet for the machine, including a plausible-looking write-up amidst its other hundreds of offerings.

The Turbo Encabulator might have been a curious footnote in the annuals of engineering history (or at least an even more obscure one) if not for an instructional film actor named Bud Haggart.

Haggart became a minor celebrity in the Detroit area for appearing in several automotive information and instruction videos. One of his regular gigs was doing how-tos for GMC mechanics.

In 1977, Haggart convinced the director and the crew to stay after the recording of a GMC Trucks training film. He wanted to record his version of the Turbo Encabulator. The “script” Haggart ad-libbed in one take was based on the original John Hellings Quick article. That original recording can be found on YouTube.

It amazed the crew, who you can hear laughing at the end of the piece. They asked Haggart how he could read the script with such a straight face. Haggart replied that “It sounds like everything else you have me read.”

Haggart was asked to reprise the role several times in subsequent years, each time with increased production value.

- 1988 - A few years later, Chrysler brought Haggart in to film a new version of his Turbo Encabulator, but this time, the script was changed to imply that the company had made the device.

- 1988 - Not wanting to be left out, Rockwell International, an American automotive manufacturing conglomerate (among other things) asked Haggart to pitch a “Rockwell Turbo Encabulator”.

- 1996/1997 - Haggart (and slapstick assistant) deliver a version of the Turbo Encabulator for Dodge Division’s Viper Automotive Master Tech Tip.

The popularity of these skits, preserved on YouTube and propagated across the internet via social media, chats, and forums ultimately inspired imitators, a brief sampling of which is below. Once you watch a few of these and trigger the algorithm to show you related videos, you quickly realize there’s an entire “Encabulator Cinematic Universe,” or ECU, for nearly every industry, interest, and profession - a brief sampling is listed below.

- 1997 - Rockwell Automation released a version of the “Retro Encabulator”, featuring Mike Kraft

- 2013 - SciShow featuring Hank Green on “The Retro-Proto-Turbo-Encabulator”

- 2016 - Path video discussing the Micro Encabulator

- 2018 - The Macquarie Telcom SD-WAN Turbo Cloud Encablulator

- 2021 - The Electro Turbo Encabulator with multiple electronic YouTubers

- 2022 - SANS ICS HyperEncabulator (featuring Mike Kraft reprising his role)

- 2023 - The crazy legal issues of the turbo encabulator

The Turbo Encabulator has found purchase in areas as diverse as photo gear vlogs and science education curricula because technology has infused so many aspects of our modern, everyday lives. As the need for change incentivizes products to move from rigid atoms to malleable bits, we find ourselves constantly confronted with the kind of technobabble and jargon that sounds straight out of one of the many Turbo Encabulator homages.

I would argue that the pace of change hasn’t sped up over the last century, not really. However, what has changed is the amount of information exposure we undergo daily, and with that exposure comes an incredible number of claims. Blogs, websites, social networks, podcasts, tutorials, videos - in an era of sophisticated “content marketing”, the amount of potential information you have access to far exceeds the amount of time you have available to consume it. And on the internet, anyone can make claims - right, wrong, or otherwise.

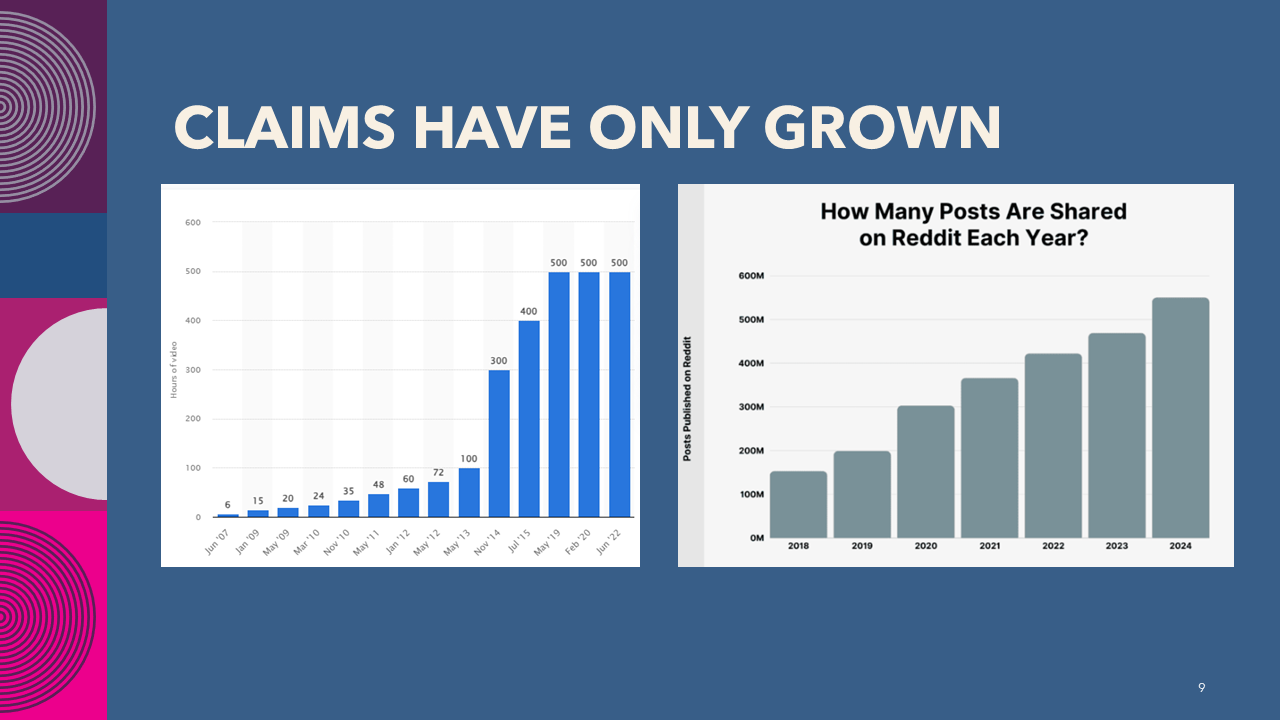

On the left is a chart showing that the number of hours uploaded to YouTube every minute exceeded 500 hours. This equates to approximately 30,000 hours of newly uploaded content per hour.

On the right is a chart showing the growth of posts made to Reddit. In 2023, an estimated 469 million posts were published on Reddit, an 11.14% year-over-year increase..

With everybody making all those claims, it becomes more challenging to be heard. As a result, those with something to say must resort to increasingly Turbo Encabulator-like approaches to stand out.

That is why so much of what you might hear about today’s technologies sounds like an excerpt from the Turbo Encabultor script. You’d be forgiven for thinking these real claims, things I’ve seen in the past week, is jibberish:

“While handling APIs using AGI is not feasible at this time, employing an ANI approach can lead to very powerful M2M APIs.”

“The Non-Fungible Token (NFT) ecosystem is fundamentally anchored in the decentralized consensus mechanism inherent to blockchain technology, specifically leveraging the immutability of distributed ledgers to authenticate and tokenize unique digital assets. NFTs exist as cryptographically secured, ERC-721 or ERC-1155 smart contracts on the Ethereum blockchain, although cross-chain interoperability with other Layer-1 protocols like Binance Smart Chain and Solana is increasingly prevalent.”

“Private AI x CPaas offer on-premise LLM deployment for organizations to ensure data privacy and security while leveraging the power of modern LLMs and Generative AI through platforms like Ollama. This solution would include on-premise (or collocated) deployment, customizable AI models tailored to organizational needs, robust security measures, easy integration with existing systems, and continuous deployment.”

Of course, ridiculous, over-the-top claims have become LinkedIn “influencer’s” stock-and-trade. Good for them. Confusing for the rest of us.

In an ideal world, we would have the time, energy, and inclination to develop firsthand experience with these various technologies. However, applying that rigor to compare and contrast what is said against our hard-won knowledge doesn’t scale to the number of claims we’re faced with. This is especially true as our careers grow and change.

Whether moving into higher management roles or becoming deeply specialized individual contributors, the reality is that we are no longer hands-on with every tool and innovation shaping online discourse. This occurs as we are tasked with guiding our teams and making strategic decisions about these approaches - approaches we may have only a surface-level understanding of if any at all. This disconnect poses one of the most significant challenges aging software professionals face—how to effectively evaluate and make informed decisions about technologies they no longer have the time or capacity to master firsthand.

One approach would become cynical: when confronted by the overwhelming number of claims, adopt a mindset that there is nothing new and that whatever the first technology we professionally mastered is the peak of practice - everything else is just unnecessary complexity.

I’m not saying that some of these recent “Make X Great Again” efforts aren’t without good reasons. However, if you read enough of the justifications, you’ll get a whiff of sour grapes, the hint of “everything was better in the old days”.

Efforts that come to mind include:

- Trunk Based Development

- Vanilla JavaScript/No-React

- Cloud Repatriation

- Moving back to Monolithic architectures after trying Microservices

I can sympathize. Nobody wants to invest their energies into something that becomes the next Google Wave or Microsoft Silverlight. The cynical approach is also straightforward to apply.

However, the danger of adopting a cynical outlook and rejecting all claims outright is that it risks missing profound and industry-altering changes - and while that doesn’t happen as often as some might claim, it does happen.

When evaluating Turbo Encabulator-like technobabble in claims, our old frames of reference might not always apply. What was once true in the past may not hold true in a different software paradigm.

Flimflam is not new. But the democratization of the internet means there are more claims than ever, with those with something to say working harder than ever to get their message heard above the crowd. That saturation necessitates that we, those of us in all manner of tech leadership, become more active as consumers - not passive conduits for the vendor, analyst, and consultant messages, but people making informed judgments of what we do see.

Evaluating new claims becomes an exercise in discerning meaningful innovation from marketing-driven hype—a skill that must be honed over time.

So how do we do that?

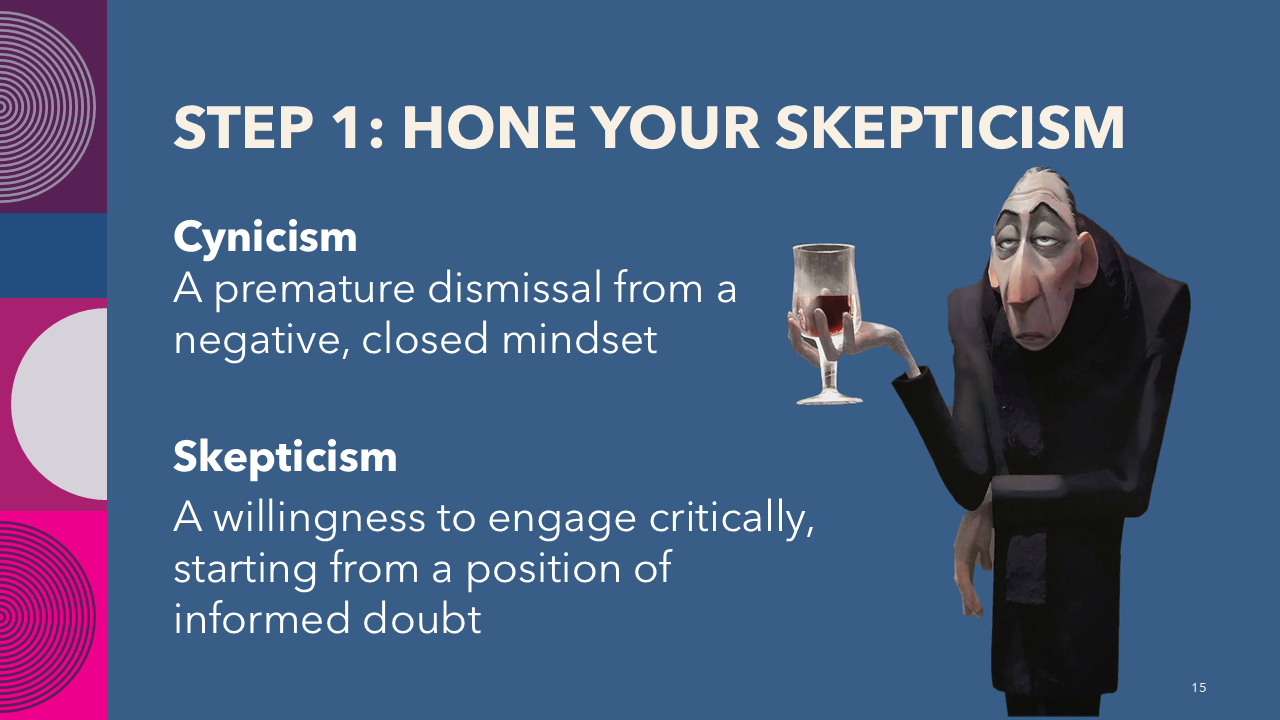

When evaluating a convoluted claim, the first step is approaching with a healthy dose of skepticism.

I should point out that skepticism is not the same as cynicism.

Healthy skepticism involves questioning and critically assessing claims, seeking evidence and reasoning before accepting them. Skeptics remain open-minded and willing to change their views if presented with compelling evidence. This approach helps evaluate technology claims objectively, without being swayed by hype or marketing, while still considering potential benefits.

Conversely, cynicism tends to dismiss claims outright, often assuming that they are exaggerated or false without engaging in critical evaluation. Cynics generally expect deception or failure, and their approach is more closed off, making it harder for them to acknowledge the value of genuinely promising technologies.

In short, skepticism is about informed doubt and a willingness to engage critically, while cynicism is about premature dismissal and a more negative, closed mindset.

Of course, not all sources are the same, and some warrant a higher degree of skepticism than others. We know (or should know) that the claim that gets the most shares or comments is not equivalent to something with the highest quality. Likewise, something published on InfoQ may be taken on more face value than whatever is at the top of HackerNews.

In the process of developing our list of trusted sources, it is also important to incorporate sources of information that will offer new perspectives and challenge our own assumptions. It is not a matter of picking fights; rather, it is about getting out of our own “filter bubble”. This may feel uncomfortable at first. However, if we’re will to entertain the claims of something potentially disruptive, we may discover that those claims may be bogus, and we have further confirmation in our own belief. Or we may find a compelling reason to change.

Ultimately, the curation of trusted sources is about practicing curiosity and self-challenge. That’s what learning is all about. You can’t understand the world, or even a tiny part of it if you don’t stretch your mind.

Companies resort to hyperbolic claims to be heard in a noisy, crowded digital landscape. Therefore, it is essential to understand how this inflation manifests to identify when it is happening.

Whether we attend conferences or scroll through influencer LinkedIn, we’ve probably heard of “Buzzword Bingo.” To help us remember the common linguistic patterns used in claims that are more “vibes” than communication, I’ve grouped the techniques into categories that spell “B-I-N-G-O.”

To help illustrate each, I’m going to highlight the parts of the Turbo Encabulator script where each rhetorical device is used.

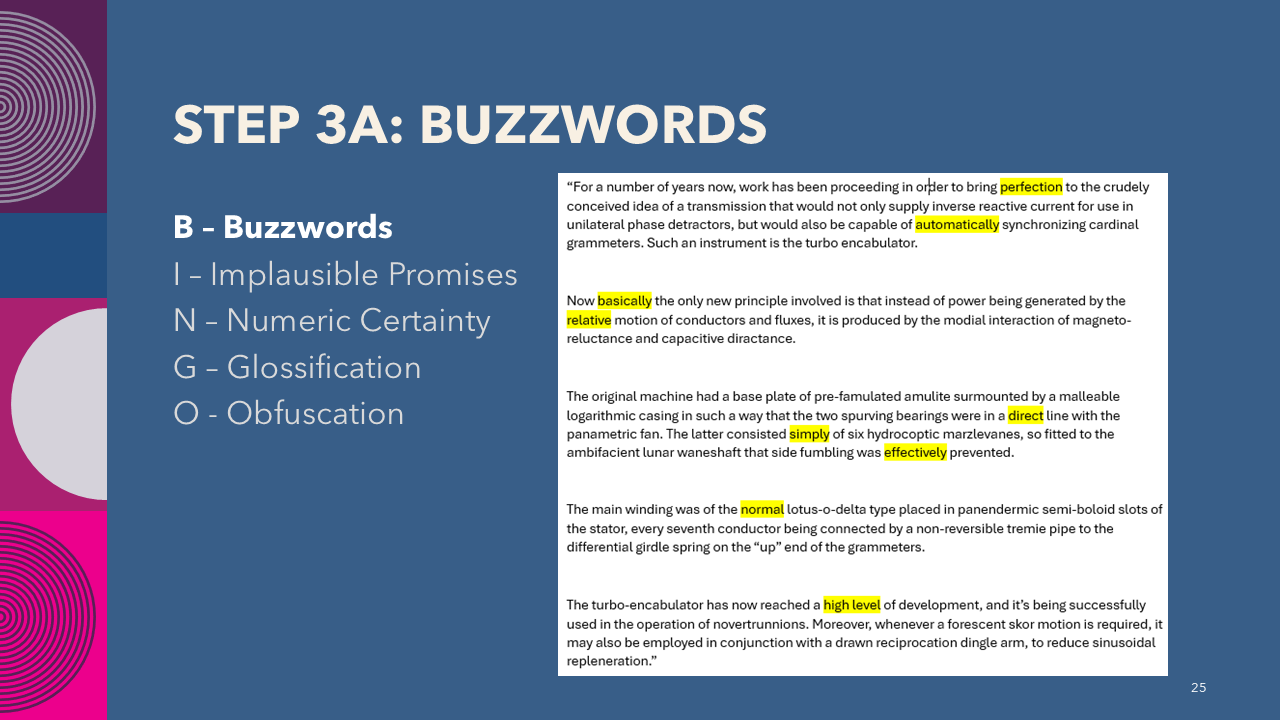

The letter “B” in Bingo stands for Buzzwords. Buzzwords are popular terms or phrases used so frequently, often in a positive or promotional context, that they lose their original meaning or become vague. They are meant to grab attention and sound appealing but may not provide much specific information. For example, words like “innovative”, “disruptive”, or “synergistic” might be used to describe almost any new idea or technology, even if it doesn’t truly revolutionize anything. Phrases like “game-changing,” “future-proof,” or “industry-leading” often sound impressive until one stops a moment to reflect on what game or industry is being talked about.

Conceptually, we all probably understand buzzwords and have a few examples that spring to mind. Let’s move on to our next category, which is a bit more nuanced.

The “I” in Bingo represents “Implausible Promises”. These are over-the-top claims about what technology can do, like “limitless potential”, or “effortless transformation.” Other examples include:

- Completely eliminate risk

- Meet any demand

- Transform your business overnight

- Results guaranteed

- Endless possibilities

With each of these, there’s an absolutism to the benefit - “limitless”, “any”, “endless” - that rarely exists in the real world. If you can add “or your money back” to the claim, what you have is an infomercial, not a viable claim.

If you spend any amount of time in the blockchain/crypto game space, it doesn’t take long to run across an “implausible promise”. But reading about the aftermath does make for some fun schadenfreude.

Speaking of absolute quantities, the “N” in Bingo stands for “Numeric Certainty”. This situation is where dubious statistics or metrics are sprinkled throughout the claim to give the language a veneer of mathematical rigor. Some examples include:

- Double Your Performance

- 10x Developer

- 300% ROI Increase

- “Five nines”

- First Ever!

Sometimes, numbers associated with a claim are valid and based on repeatable methodology. When misused, however, they are either exaggerated or cherry-picked to impressed.

Numeric certainty appeals to a very specific type of reply guy on miniblogging platforms. The misuse of statistics made on Twitter claims played a important part in the Lambda school scandal.

The “G” in Bingo stands for “Glossification”. This is when new words are coined to “borrow” a positive associate with another thing, whether that thing is another beloved trend or well-received product. It’s like the trend of startup companies registering ‘.io’ domain names in the 2010s to imply how innovative or tech-forward they are. Nowadays, the “cool” domain is “.ai.”

In the late 1970s and 1980s, Microsoft was not the only software company that sported the “soft” suffix to clearly attach itself to the personal computing software wave. Twenty years ago, you’d add an “e” to your product to connote that it was somehow networked. In the iPod era, many companies prefixed their products with “I” to evoke the positive aspects of Apple’s industrial design.

“Crypto” is a habitually abused glossification prefix. Terms like “HyperScale” or “Serverless” are other examples of glossification that aren’t brand names. The addition of “Turbo” in “Turbo Encabulator” is an example of glossification.

But glossification isn’t limited to written language. Borrowing positive connotations extends to body language, as well. But just because a company leader talks like someone with immense impact doesn’t mean the tech can walk the walk.

Finally, we’re to the final character in Bingo. The “O” stands for “Obfuscation”. Obfuscation uses overly complex or technical-sounding language to confuse or impress, often hiding a lack of real substance. It’s designed to make something sound more advanced or important than it really is. Examples include phrases like “leveraging multi-cloud quantum synergies” or “immutable distributed ledgers” - things that may sound impressive but don’t necessarily convey meaningful or clear information.

Obfuscation is a close cousin, but different than buzzwords. Buzzwords are overused, trendy terms that no longer have specific meanings. Obfuscation, on the other hand, is about using complexity to obscure or confuse.

John Green is the author of many books, including The Fault In Our Stars. He is also one-half of the Vlogbrothers. While playfully discussing parts of speech, he stated, “language doesn’t exist to oppress us. It exists to promote the clarity of expression.”

Sadly, not every one that speaks seeks to clarify.

The Turbo Encabulator is an eighty-year-old engineering joke whose jargon-filled meaninglessness cuts too close to home. Technobabble is even more challenging today in a world of claims and counterclaims. However, with a few commonsense steps, including the ability to recognize the rhetorical tricks as they’re presented, you’ll be able to enjoy the joke rather than become the butt of it.

Thank you for the time and the opportunity to share.