The “Ironies of Automation” Paper Defines a Paradox of Automation

Ruth Malan, a software architecture and systems consultant, organizes the wonderful “Papers in Systems” discussion series (I’ve also taken her Organizational Design Masterclass). During those virtual Zoom sessions, facilitators present a noteworthy paper, and the assembled group share their thoughts on the piece. It can be an eye-opening experience, if for no other reason than to realize that annoying boogeyman you thought you faced alone happens to also be hiding under a lot of other people’s beds.

The latest installment, led by Alex Ptakhin, covered Lisanne Bainbridge’s 1983 paper, Ironies of Automation. As Bainbridge says on that site:

“This was written before I had a personal computer, let alone a mobile phone. Of course there has been much process in the last 40 years in the technology of providing both operators and writers with support, but evidently the question remain.”

And it is true. While Bainbridge’s observations were on the operation of industrial control systems, she might as well have been talking about how today’s organizations approach AI.

Brainbridge’s begins with an apparent paradox: that by adding automation to a system increases the dependency on a trained human operator rather than decreases it.

“The classic aim of automation is to replace human manual control, planning and problem solving by automatic devices and computers. However, as Bibby and colleagues (1975) point out : “even highly automated systems such as electric power networks, need human beings for supervision, adjustment, maintenance, expansion and improvement. Therefore one can draw the paradoxical conclusion that automated systems still are man-machine systems, for which both technical and human factors are important.” This paper suggests that the increased interest in human factors among engineers reflects the irony that the more advanced a control system is, so the more crucial may be the contribution of the human operator.”

The automation paradox is that automation is pursued to remove human inefficiencies, yet highly automated systems still require human supervision, adjustment, maintenance, and decision-making. This is because operators are often left with tasks that are difficult to automate, such as handling emergencies or diagnosing failures. And the more sophisticated an automated system becomes, the more crucial human involvement may be and the more cognitively demanding the job becomes, especially in abnormal situations.

The bottom line is that rather than removing human dependencies, automation often shifts and amplifies them. If you’ve ever been part of a DevOps or Platform Engineering transformation effort that started with great fanfare and then found yourself drowning in YAML only a few years later, you have experienced this phenomenon personally.

Today’s Automation De jour: Agentic AI

Which makes this a great moment to talk about Agentic AI. By now, most people have had some first-hand experience with generative AI. Even if you aren’t generating images with Midjourney or emails with ChatGPT, you’ve probably seen generated summaries at the top of your search results, had it pop up in your office suite, or discovered that a VC swapped it for the toy in your breakfast cereal.

Agentic AI, an increasingly buzzy term since being coined last November, takes this a step further. It refers to programmatic systems that can autonomously take actions, pursue goals, and make decisions without human intervention at every step. Unlike people’s use of Claude or ChatGPT’s chat interfaces, which respond when prompted, agentic AI actively engages with its environment, initiating actions and persisting toward objectives.

In describing Agentic AI as the highest level in their enterprise AI maturity model, Michael Coté and Camille Crowell-Lee describe Agentic AI operation as:

- Breaking down a request into a plan.

- Executing each step (calling APIs, running microservices, executing code).

- Analyzing the outcomes, adjusting if needed.

The example they use to describe how this works in practice is, basically, the plot of those Matthew McConaughey Salesforce ads:

“Think back to the restaurant reservation app. First, the agentic application would reason out that it needs to find your preferences for a restaurant. This might mean asking you directly, but it might also mean looking at your past reservations and reviews you gave. Perhaps you like sitting outside, but is it raining? The intelligent application would look up weather for your area. And so forth. Once this “research” is built up, the agentic AI will then use its tools to look up available tables at matching restaurants, and if it finds a good match, make the reservation for you, again by making an API call. Of course, a human (that’s you!) can step in at any point to move the workflow along or modify it.”

Ramifications Of Looking At Agentic AI Through an “Irony of Automation” Lens

Note the “step in at any point” statement. Suppose we apply Brainbridge’s Ironies of Automation truths to Agentic AI. In that case, we can anticipate several key ramifications - many of which mirror or even amplify the problems previously seen in automation-heavy systems.

The Oversight Paradox: Humans Will Still Be Needed But in More Challenging Ways

Expectation: Agentic AI systems will be fully autonomous, reducing the need for human intervention.

Reality: If you thought war-room debugging was bad now, just imagine all the comradery you’ll get from HAL 9000 after the pager-duty notification goes off at 2am. Humans will still need to monitor, correct, and override AI behavior, but this task will become more complex and cognitively demanding because:

- AI decisions are made using logic that may be opaque or non-deterministic.

- Failures will often occur at the edges of AI capability, where human expertise is weakest (since humans will have been out of the loop).

- Just as pilots struggle to take over when autopilot fails, humans will be asked to intervene in situations they are least prepared for, often under stress.

Ramification: AI oversight will become a specialized, high-cognitive-load task rather than a simple supervisory role. Human skills will atrophy while reliance on AI grows, at least until intervention is suddenly needed in a high-stakes situation.

The Black Box Monitoring Problem

Expectation: AI agents will self-monitor and self-correct, reducing human burden.

Reality: “Explainable AI” is still one to two years away, just like how Level 5 self-driving cars are gonna happen any day now and this will be the year of Linux on the desktop. Monitoring AI will be qualitatively different from traditional automation because:

- AI decision-making is often opaque (e.g., large language models, reinforcement learning).

- AI operates in complex, evolving environments, making the establishment of clear rules for acceptable behavior harder.

- AI doesn’t just “execute” tasks like traditional automation - it autonomously decides how to execute them, creating failure modes that are hard to anticipate.

Ramification: Humans will struggle to monitor AI decisions in real-time, just as DevOps engineers struggle with brittle, YAML-driven pipelines. The very complexity AI is meant to reduce will resurface in debugging its behavior.

The “Skill Rot” Problem: Humans as Unpracticed AI “Owners”

Expectation: AI will handle most routine decision-making, freeing humans for “higher-level” strategy.

Reality: Remember the Y2K bug, when enterprise recruiters beat down retirement home doors for Fortran and Cobol programmers? What if we recreate that 52-card pickup between all our subject matter experts and our business-sensitive context on a recurring basis? When humans are removed from day-to-day operations, their ability to intervene effectively in edge cases deteriorates, similar to:

- Pilots losing manual flying skills due to autopilot dependence.

- Process operators in automated plants struggling to diagnose failures because they lack hands-on experience.

- Software developers becoming automation babysitters rather than programmatic experts.

Ramification: Human expertise will degrade over time, just as in other automation-heavy fields. This is dangerous because when AI fails, humans will have to step in, but they’ll be less capable of doing so.

The Brittle Autonomy Trap

Expectation: AI systems will become robust and handle more complex tasks over time.

Reality: You asked the AI to buy lunch for the seaside offsite, and now it’s sending a DoorDash driver with 48 pounds of frozen shrimp to your office. Over-automated AI systems could become brittle, meaning:

- AI can handle predictable tasks exceptionally well, but when unexpected scenarios arise, it collapses catastrophically.

- AI can mask failures - just as industrial automation can compensate for a failing machine until a catastrophic breakdown.

- Humans may not realize AI is failing until it is too late.

Ramification: AI will make systems appear more stable than they are until a major failure reveals hidden fragility, just as DevOps pipelines and industrial automation have done in the past.

The Ironies of Agentic AI

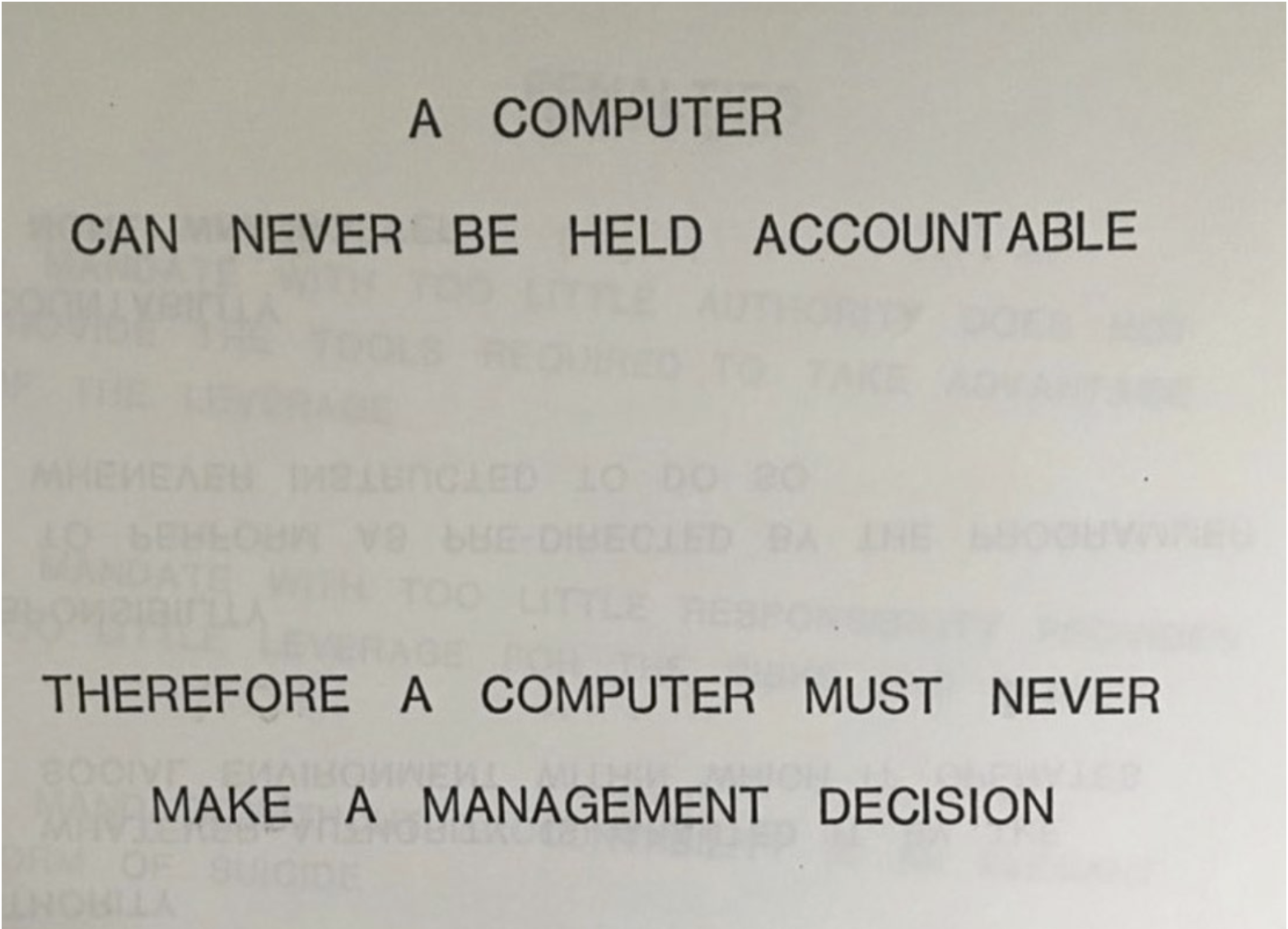

In 1979, a presentation at a regional IBM office led to one of the most memeable images of our age:

While many have attempted to track the original author, the slide’s origins appear to have been lost to a flood in 2019. But the sentiment is true: people need to be accountable, not just to provide the “one neck to wring” when things go wrong, but because AI has no concept of morality, ethics, or law. Human judgement in these systems is a feature, not a bug.

The more we delegate to AI:

- The more challenging it will be for humans to intervene effectively when needed.

- The more brittle and opaque our systems will become.

- The greater the risk that AI will exacerbate rather than eliminate human errors.

Just as Bainbridge’s Ironies of Automation warned that automation doesn’t eliminate human problems but shifts them, Agentic AI may increase a company’s dependence on human oversight, but in a harder, not easier way.

Executives, especially under current economic pressure, are keen to buy Agentic AI’s to achieve additional efficiencies while reducing employee overhead. However, the actual outcome may be systems where people are still crucial, but in ways they neither anticipated nor are well-prepared for.

Generative AI systems have utility. In fact, I used several of these tools to help write this piece: asking where the central argument could be stronger, looking for related examples to address gaps, and correcting the overall grammar. And from industrial robots on assembly lines to inbox spam detection, there are copious examples of automation being a net positive in modern life; the automation doing the jobs that are either too tedious, dangerous, or unfulfilling for human effort.

These agents will be attempted. That bandwagon has left on autopilot CoPilot™. However, as those responsible for manifesting those systems within organizations, it is imperative that we heed Bainbridge’s “Ironies of Automation” and don’t blindly automate everything. When automation is called for, we must keep human operators engaged through training, simulation, and periodic manual operation while designing automation to fail in clear and obvious ways to prompt easier human interventions. If we can do that, we’ll support and sustain human expertise, not erode it.

Update 2025-06-04

There was a recent exchange on Mastodon that, I thought, reflected this article’s premise. While linking to an article on requiring drivers in self-driving vehicles, Brian Marick noted, “Is there any safety lesson more basic than ‘even trained humans are really bad at staying focused, ready to intervene, when the need for intervention is infrequent’? And yet here we are, making the same damn mistake again.”

Donald Ball responded, “These systems are lousy at producing safety but aces at producing scapegoats to serve as the accountability sink.”

Update 2025-10-11

Pavel Samsonov, in a lovely piece, describes how the phrase, “Humans in the loop” is **a thought-terminating cliche.