In the wake of Cambridge-Analytica, Facebook seems to be taking the wrong lessons from the incident (or, if I’m cynical, they’re skewing in a direction that cements their market dominance). They are correct that the loss of trust is so much bigger than whatever terms of service Cambridge Analytica violated. However, the stated conclusion that there is a binary relationship between data portability and privacy - that either everything must be shared or Facebook controls everything - is wrong.

Intro

Last week, concerns over Facebook’s data collection practices reached an all-time fever pitch. I had intended on sharing my thoughts, along with a handful of recommended takeaways for API providers, as part of my Net API Notes. However, the longer I compiled breaking news, the longer the piece became. Eventually, it seemed warranted to break Facebook off into its own dedicated post.

I’ve tried to be thorough, but “uncritical” set sail awhile ago. I’m biased. People, like techno-sociologist Zeynep Tufekci, raised the alarm years ago, when meaningful action could have been taken. I left Facebook around the same time over concerns on the power uber data aggregators wield.

Despite those protestations, Facebook’s practices continued. It doesn’t appear that the internal conversations ever switched from “can we?” to “should we?” And now the mob, embittered and frustrated by the cultural malaise of the moment, are coming with torches and regulatory pitchforks.

About. Goddamn. Time.

Background

Mid-March, The New York Times reported that Cambridge Analytica improperly acquired the private data of approximately 50 million Facebook users. It then, subsequently, used the psychological profiles it created with the data to target voters on behalf of the Trump campaign during the 2016 presidential election. The Obama campaign, in 2012, also ingested Facebook relationship data. However, while the Obama campaign was transparent that people were giving their information (and their friends’ information) to the cause of re-electing Obama, the Trump campaign used data culled from a personality quiz app.

This app used the 1.0 version of the Facebook’s Graph API. That version launched in April, 2010 and allowed developers to “not only see the social connection between people, but see and create the connections people have with their interests - things, places, brands, and other sites”.

Very little information is needed before profound insights can be inferred about a person. A Carnegie Mellon study has shown, 87% of Americans can be positively identified using only a 5-digit postal code, gender, and date of birth. Full name, postal code, and date of birth equate to voter rolls, which themselves are sold by many states. Using nothing but likes, researchers Michal Kosinski, David Stillwell, and Thore Graepel have successfully shown they can predict a wide range of sensitive personal attributes including “sexual orientation, ethnicity, religious and political views, personality traits, intelligence, happiness, use of addictive substances, parental separation, age, and gender”.

Further, version 1.0 of the Graph API didn’t just make information about a specific user available; it allowed “extended permissions”. This feature allowed approved apps to request a range of users’ friends, along with their information. This additional information did not require the consent of those friends before it was shared. In addition to Personally Identifiable Information (or PII), this friend information included education, groups, hometown, interests, location, relationships, religion, work history, etc. Having understanding of information flow is powerful; according to one study, ‘95% of the potential predictive accuracy attainable for an individual is available within the social ties of that individual only, without requiring the individual’s data’.

A University of Cambridge professor, Aleksadr Kogan, created an app called thisisyourdigitallife. Built using Facebook’s Graph API, he seeded the initial userbase with people paid through Amazon’s “Mechanical Turk”. Subsequently, around 270,000 people were paid between $1 and $2 to download and use the personality quiz app. Through the use of ‘extended permissions’ the initial 270,000 users resulted in 50 million populated profiles; profiles containing the names, dates of birth, employment history, likes, and more. Aleksadr then gave the information he collected to Cambridge Analytica. Technically, only the last step violated Facebook’s rules, which prohibit selling or giving away data collected by a third-party app.

Graph 1.0 was deprecated on April 2014 (and access ended entirely in 2015). The second version of the Graph API, while providing information for the conscenting user, no longer has extended permissions. However, the data collected by external entities during this time cannot be expunged; revoking access does nothing to the apps that might have had access and saved themselves a copy. The data is out there, on who-knows-how-many private servers, with the potential to be purchased, aggregated with other datasets, and weaponized for future scenarios.

In fact, as the author of the Facebook game ‘Cow Clicker’ stated, “all the publicity around Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica crisis might be sending lots of old app developers, like me, back to old code and dusty databases, wondering what they’ve even got stored and what it might yet be worth”.

Furthermore, the abuses didn’t stop when Graph 1.0 was fully shutdown in 2015. Other Facebook products, like Instagram’s API, still exhibit similar behavior. In March, 2016, Facebook expelled a group that was using its API to scrape data about people who expressed interest in Black Lives Matter. The group had been selling the data to police departments. At the end of the same year, the Department of Housing and Urban Development launched an investigation following concerns that Facebook’s advertising tools allow real estate advertisers to discriminate users according to race. Facebook has also admitted to collecting call and text message history of users who own Android phones (while users were asked if they wanted to import their phone contacts, it was not obvious to many users that they were agreeing to have their cell phone activity recorded).

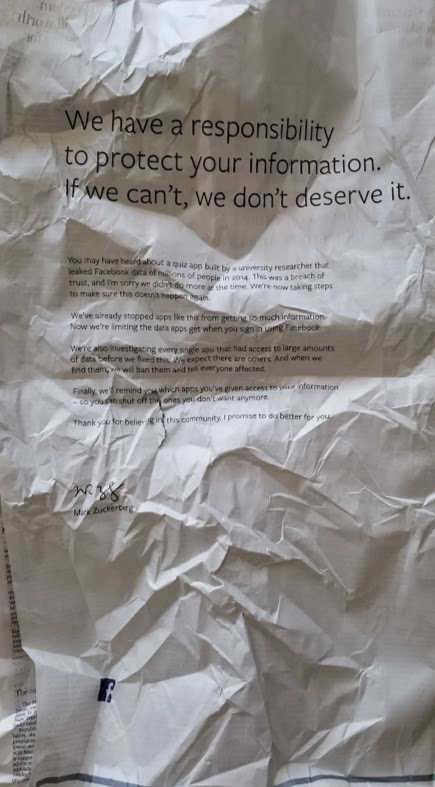

Mark Zuckerberg responded last Wednesday afternoon, outlining reactive steps to the situation: Facebook would investigate old apps that used v1.0, further restrict access to data, and give more transparency and control to end users.

Meanwhile, Facebook and Cambridge Analytica have threatened to sue the journalists that broke the original story. This seems, primarily, over the erroneous use of the word “breach” in the course of describing events; if determined to be a data breach (which this wasn’t), the company could face fines.

Conclusions

Frustratingly, Facebook seems to be taking the wrong lessons from the incident (or, if I’m cynical, they’re skewing in a direction that cements their market dominance). They are correct that the loss of trust is so much bigger than whatever terms of service Cambridge Analytica violated. However, the stated conclusion that there is a binary relationship between data portability and privacy - that either everything must be shared or Facebook controls everything - is wrong.

Techdirt summarized the round of media interviews that Mark Zuckerberg did, where he said:

“I was maybe too idealistic on the side of data portability, that it would create more good experiences — and it created some — but I think what the clear feedback from our community was that people value privacy a lot more.”

Later, he bemoans having to make these kinds of tradeoffs:

“I guess I have to, because of [where we are] now, but I’d rather not.”

If consumers had control, it would take Mark out of the leadership role that he is, apparently, uncomfortable playing. Why can’t someone easily be able to bulk-delete “likes” older than a year? Why is it necessary for Facebook to retain work history older than the last employer? Sexual orientation, race, and religious affiliation can get someone killed - so why can’t people indicate that these should never be stored, or even inferred - as part of their profile?

The most valuable part of Facebook, for an individual, is not the status updates, or the images uploaded - it is the network of connections they’ve built. This is why so many apps, unable to get the social graph from Facebook, resort to the kludge of the “access your contacts” email workaround. If the individual chose, why couldn’t they take those relationships (sans ‘extended permissions’ data) with them somewhere else?

Rather than allow apps to hoover up the kind of information useful for psyops, why not allow developers to create 3rd party tools for permissions configuration, the kind Cory Doctorow wrote about?

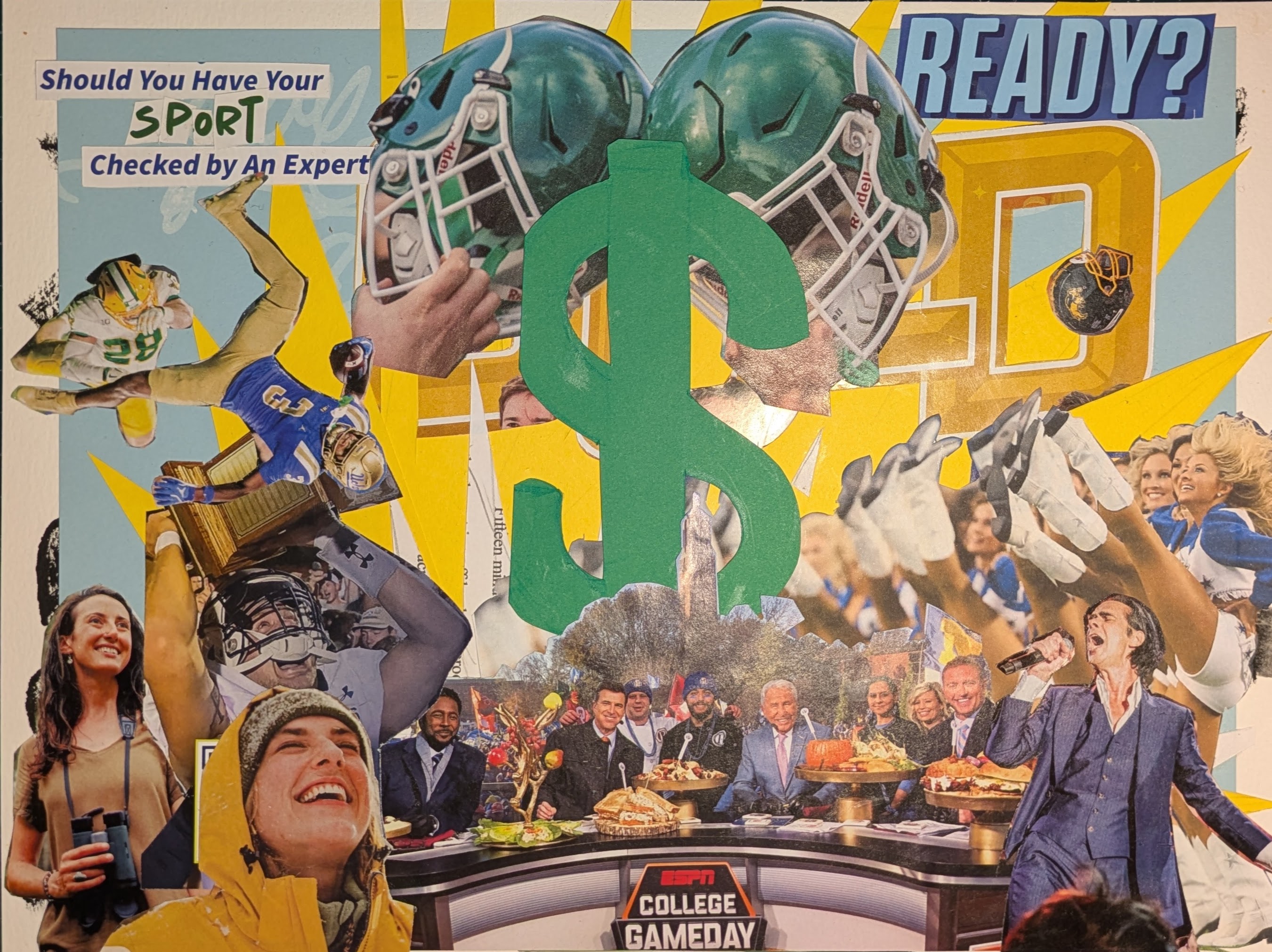

Unfortunately, because there is little market incentive for Facebook to do so. Till now, the profitable thing has not aligned with the right thing. As Doc Searls has written, this is a problem not just for Facebook, but for an entire online publishing industry dependent on building advertising panopticons for revenue growth.

Regulation, above and beyond what currently exists, is coming. It could make a difference. However, ideas currently swirling entrench Facebook as the market leader, with little likelihood of alternatives arising. An example is the European ‘General Data Protection Regulation’ (GDPR). It goes into effect May, 2018. Some have hailed it as progress toward defining when user consent is necessary. It also has provisions for data portability. However, there are already workarounds devised, with the social graph considered a “legitimate interest” of the social network. As a ‘legitimate interest’ of the business, it is not privy to export.

As Techdirt summarized:

“Solving” the problem isn’t going to be solving the problem for real – and it’s just going to end up giving Facebook greater power over our data. That’s an unfortunate result.

What we need is thoughtful, not knee-jerk, regulation. We need consumer-friendly policies that promote the principles of the open web and eschew monopolies. We need to treat personal data with the kind of care and responsibility that we do with powerful, and potentially dangerous, things in the real world. And we need to look for answers outside of Facebook, because there’s few incentives to drive the necessary change from within.