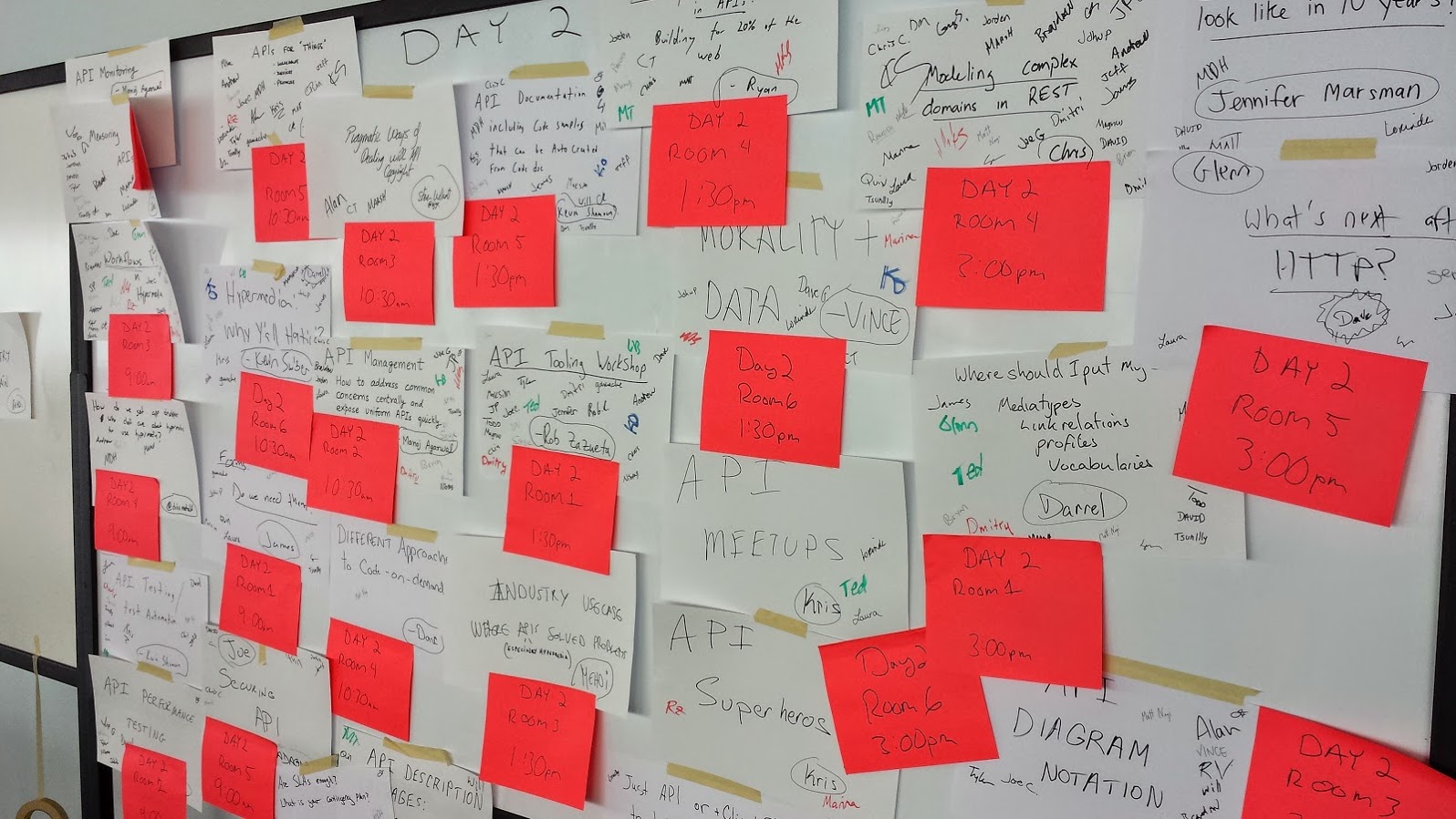

I recently had the pleasure of attending the 2014 API Craft Conference. Despite the compelling nature of the content, the host city, Detroit, could not be ignored. I came for the ideas and left haunted by the venue.

What happens when a city struggles to wear the infrastructure built for a population twice the current size? It's not a particular building, or block, or area; the entire downtown is a hodgepodge of modern, inhabited buildings standing alongside achingly beautiful, yet derelict, ruins. The fluted columns and ornamental decorations speak to times that have clearly past. These buildings' deaths are now marked by a wreath of semi-permanent plywood barriers resting about their base, barring entrance. All copper has been stripped and sold. All windows removed and boarded up (if there was money to do so). In some cases it is obvious where there have been fires. Without any money for proper cleanup, netting is fixed around the critical wounds to prevent ash from breaking off and raining on what pedestrians might be below. Cities are normally in a constant state of reinvention. It is shocking to see one where the finality of yesteryear does not give birth to the banality of today. That's not the way we're accustomed to the story going. It induces unease. The actor has gone off script; we no longer have a clue how this is going to play out.

How bad is it? When water services were recently shut off, gallons were shipped into the city from neighboring Canada. A cost saving measure to install cut-rate batteries into parking meters backfired. It has left half of the parking meters out of order, further diminishing revenue.

And yet people are still people. While I waited along the waterfront, an older gentlemen stopped and struck up a conversation. As he moved to leave he said:

"I still believe in Detroit."

Whether in Detroit or elsewhere we are the same: we endure the trials of today in hopes of a better tomorrow.

The experience compelled questions. Ruin on a city-wide level doesn't happen overnight. Nor is it usually caused by a single event. Detroit was presented by a constant litany of societal change and, systematically, it made poor decisions. How did this Detroit happen? And are there lessons here that could apply to software?

Debt had always been Detroit's Achilles' heel. Administration after administration used it to bridge gaps between diminishing revenue and the cost of maintaining existing levels of municipal services. A fleeting bit of financial success in the 90s, however, allowed the city to borrow without discretion. Detroit's debt ballooned to 8 billion. This, eventually, caused the city to declare bankruptcy last July.

Any developer is familiar with tech debt. These are the decisions we make in the name of expediency. We receive immediate software gratification knowing we'll have to pay for that incurred debt at a later time. It may be foregoing test creation for time-to-market advantage. It may be leaving documentation for a later, less-busy date. It may be knowingly opting for today's simplicity over tomorrow's scalability.

The discussion is pertinent to APIs. Much of the current API boom was driven by app store development. These native apps caused development of narrowly-defined APIs around existing processes. In these situations the relationship between consumer product and API provider is 1-to-1. Often the same team provides both pieces. There is no information that is out of band; the entire development pipeline is within the purview of the same organization.

Hypermedia seems completely extraneous for this group. Link relations to communicate affordances, semantic meaning for self-documenting responses, and hypermedia as the engine of application state (HATEOAS) solves a problem that they don't have. From their perspective, yes, hypermedia is bullshit.

Debt can be a useful tool. But, as in the case of Detroit, it restricts future possibility. The next wave of API development is not like the previous one. New services, powered by automatic machine discovery, will have different expectations of affordance communication. The Internet of Things, although API driven like the native app revolution, will be an order of magnitude bigger. As the diversity of API consumers extends beyond the browser, end-of-life horizons will extend into decades.

Building single-consumer APIs is a form of technical debt. They're expedient for today. But, like Detroit's budget approach, ineffectual tomorrow.

I know it can be hard to predict a software's path after it launchs. Guessing is even harder when the world has grown an additional decade of technological thickets. Hypermedia suggests a helpful set of features for future-proofing an API. The extra upfront labor it entails avoids the technical debt of tomorrow. The promise is not fulfilled yet; much of the conversation at API Craft was admitting the problems with the scene so as to address them. But I'm human. I hope. I still believe in hypermedia.